Image Courtesy: The Excelling Edge

Mental Training isn’t new to the world of elite performance. The Chicago Cubs hired Dr. Coleman Griffith in the 1950s. The U.S. Military Academy at West Point established a long-standing mental training program in the 1980s. The U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee (USOPC) maintains a staff of sport psychology trained professionals to help U.S. athletes excel on the world’s biggest stages. However, there is a new frontier that is transforming the game of athlete performance. Before we dive in let me give you a little background.

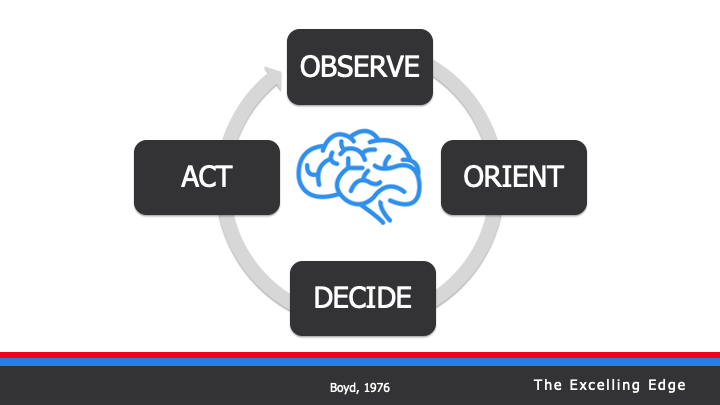

The OODA Loop and Athlete Cognition

U.S. Air Force Colonel John Boyd first published his famed OODA loop in 1976 as a training framework. The intent was to train fighter pilots to think faster than the enemy, so they could ultimately kill and survive.

OODA stands for:

- Observe

- Orient

- Decide

- Act

While developed for fighter aviators, the concept applies to athletes too. Essentially, if an athlete moves through this loop faster than her opponent, she has a competitive advantage. Note that this loop can happen in fractions of a second. And the cycle is continuous.

For example, a baller dribbling down the floor, seeing an open cutter to the basket, and making the pass for a layup. Or a goal keeper picking up on the postural cues from an attacker, anticipating the shot, and making the save.

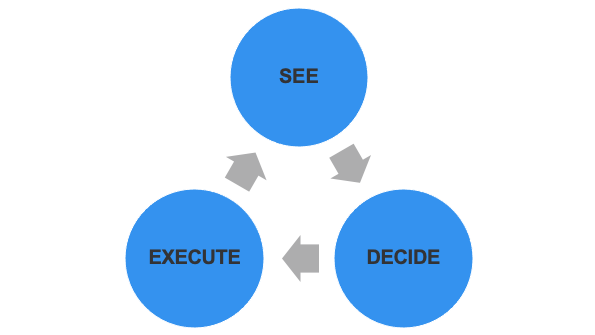

Today, fighter pilots speak of this as, “perceive, decide, execute,” as the OODA Loop has become too much of a buzzword. Regardless of the language, the principles remain the same. In fact, Dr. Len Zaichkowsky and Daniel Peterson framed the athlete cognition cycle comprising three parts, ” Search – Decide – Execute.”

Where do Mental Training and an athlete’s Cognition Cycle intersect?

The reality is that mental training can significantly influence an athlete’s cognitive efficiency – how quickly she or he progresses through the cycle (Search – Decide – Execute).

- A athlete who is confident [link] will move through their cycle quicker.

- An athlete who is anxious [link] will move through their cycle slower.

Make sense?

By equipping athletes with the mental tools, skills, and plans they need to get more out of practice and compete with consistency, mental training also impacts an athlete’s cognition cycle.

The Next Frontier in Mental Training

However, there is more to training an athlete’s brain than equipping them with mental skills. Please don’t misunderstand me. I’m not discounting the importance of mental performance training. It is my career. But there is more to gain, more to train, and more we can do to unleash an athlete’s potential.

The best part is each of the three components of this cycle (search – decide – execute) can be trained!

Training Athlete Cognition

I was invited to a girl’s basketball signing day event, in which the team’s star point guard signed her letter of intent to a Division 1 University. Afterwards, the coach was lamenting his loss and recounting the characteristics that made this player special. He noted her “court vision” and “ability to anticipate on the floor.” When I shared with him that those attributes were trainable, he nearly laughed in disbelief.

But the research is clear that an athlete’s cognition cycle is trainable. In future articles, we’ll get into more detail. But allow me to give you an overview.

The Next Frontier in Mental Performance is training athlete cognition (how athletes see, decide, and execute).

See

Over 80% of the sensory input athletes rely on to compete is visual. Athletes with superior visual skills tend to perform better and achieve higher levels of competition. More importantly, those visual skills can be improved. For example, Clark JF et al. (2012) demonstrated that visual training improved players’ batting averages.

Sports Vision Training (SVT) targeting foundational visual skills such as saccades (quick focal eye movements), depth perception, and pursuits (tracking a moving object) can be integrated into an athlete’s daily training regimen (Cincinnati team). Today there are a number of effective digital training techniques that athletes and teams can take advantage of (Appelbaum and Erickson, 2016).

Decide

An athlete’s ability to decide relies heavily on how well they perceive (the Search segment of the cycle) within their environment. It takes 284 milliseconds for a baseball player to process a fastball. For context it takes 400 milliseconds to blink. The margins are slim. Only then can a decision be made. Time, uncertainty, complexity, ambiguity and risk are all factors that influence decision making.

Williams and Ford (2013) defined decision making as “the ability to plan, select, and execute an action based on the current situation and the knowledge possessed.” While there are multiple theories, research demonstrates that training executive functions such as working memory and pattern recognition speed decision making. However, speed isn’t the only factor to consider.

Accuracy is also paramount in the equation. The more options, the slower athletes are to decide. A 2017 study of elite youth soccer players revealed that elite players chose the best option 74% of the time (Raab & Johnson). When pressed for time, players further reduced their options and actually increased the quality of decisions. Too often, athletes overthink decisions rather than trusting their instincts.

Quick moving, short-sided games are a simple way to speed up the decision making process in practice. Decision-oriented visual-motor training with tools like HECOstix or Blazepod are fun ways to train binary decisions (Go/No Go) with eye-hand coordination drills. Restricting visual input using strobe eyewear is another great way to speed up visual processing speed and thus, anticipation and decision making.

Execute

We often think of reaction time (i.e., execution) as a mechanism of fast twitch muscle fibers firing on command. However, in reality, much of the neurophysiological process of reaction to a stimulus is cognitive. Before an athlete reacts, she must first perceive the trigger, identify the intended target of interest, decide how to react, build the motor program to react effectively, then tell the motor cortex to implement the chosen response (Dudman & Krakauer, 2016).

What speeds up reaction time? If roughly 70% of reaction time is cognitive and 30% is physical, then it stands to reason that targeting improvement in the 70% would yield the greatest gains. In my experience this is countercultural. Yet, also in my experience, it works. For example, training the visual and perceptual (i.e., processing and anticipation) abilities of military operations led to approximately 10% improvement in reaction time. In baseball, that equates to giving a hitter 43 more milliseconds to make a decision and react to a pitch, increasing cognitive efficiency and the likelihood that the hitter puts the ball in play.