Image Courtesy: Science Focus/Getty Images

The last couple of years for many of us has been a series of trying to make plans, only to have to throw them away in light of changing conditions outside of our control. We have had to learn how to re-shuffle our schedules, adopt new habits and routines, and re-prioritize our goals and behaviors to fit the moving targets of external demands on our time and energy. This goes for demands related to work, daily life, family & friends, as well as etching out a crevice of time somewhere for our own physical and mental training for health, fitness, and/or performance.

My own training priorities have certainly shifted in recent years toward optimizing for health & fitness, and gaining an appreciation for words like ‘longevity’, ‘durability’, and ‘resiliency’. Rather than peak competitive performance.

Endurance competition must include a high level of fitness, but a high level of fitness does not need to include competition.

I don’t think Performance and Health are mutually exclusive in terms of exercise training. I think of them as two book-ends along a spectrum of Fitness. In which there is a lot of overlap in training that will improve toward both priorities. However, to some extent optimizing for one will necessarily mean de-optimizing for the other.

As I’ve been thinking about this spectrum of training for fitness, I’ve tried to establish a consistent training routine for myself that I can use a foundation – a home base that I can return to when the conditions around me suddenly shift and once again I have to throw out my plans and consider how to re-prioritize my future in the short, medium, or long-term.

The foundation for this sustainable training routine should be parsimonious, in that it should be both optimally simple and optimally effective. We can add variety and complexity like hard-start or intermittent (30/15) intervals, over-under, heat training, cadence drills, and all the rest. But the foundation of the routine should be utterly simple. When in doubt, our home base has a straightforward workout prescription that we can fall back to.

It should be effective toward improving metabolic health and endurance fitness with a long-term focus on compounding adaptations, which can be cycled through to avoid training stagnancy. Specific tapering and race blocks can then be introduced to optimize for short-term peaks in performance if desired.

It should have a consistent periodized structure on a daily (session), weekly (microcycle), monthly (mesocycle), and multi-month (macrocycle) basis to prioritize gradual, compounding adaptations. But it should have the flexibility to shift and accommodate the inevitably competing demands on time and energy that will arise.

Of course, the foundation for this training plan should be informed by the consensus of systematic evidence, but not beholden to only what can be statistically verified. We should appreciate what works for us might not work for a rigorously controlled study group, and vice-versa. Training should be individualized for the individual. Efficacy does not necessarily imply effectiveness. What works in practice may not work in theory.

With those scattered philosophical thoughts in mind, here is a basic template for what I currently consider to be a solid, simple, sustainable training plan that can be individualized, modified, mixed around, and repeated near ad infinitum. This can be used as a foundation for whatever training goals we have, be they focused on performance with a specific peak event/race date in mind, or more about sustaining general health, fitness, longevity, and resiliency.

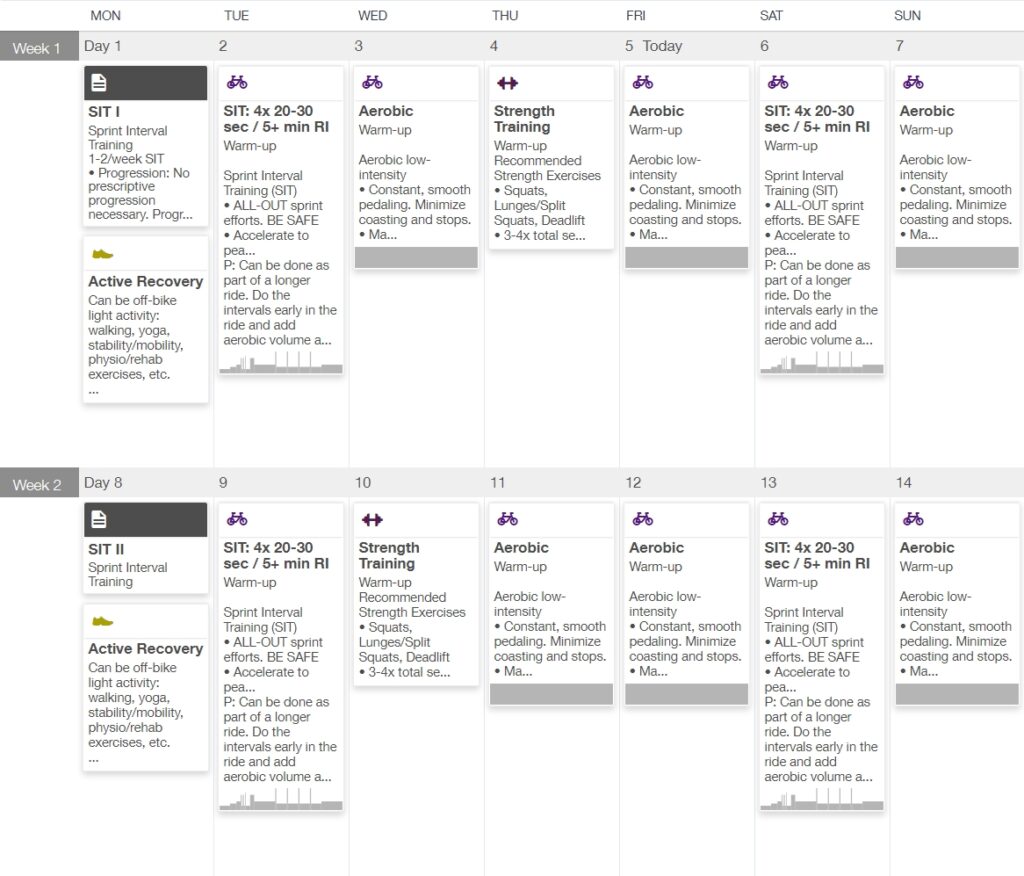

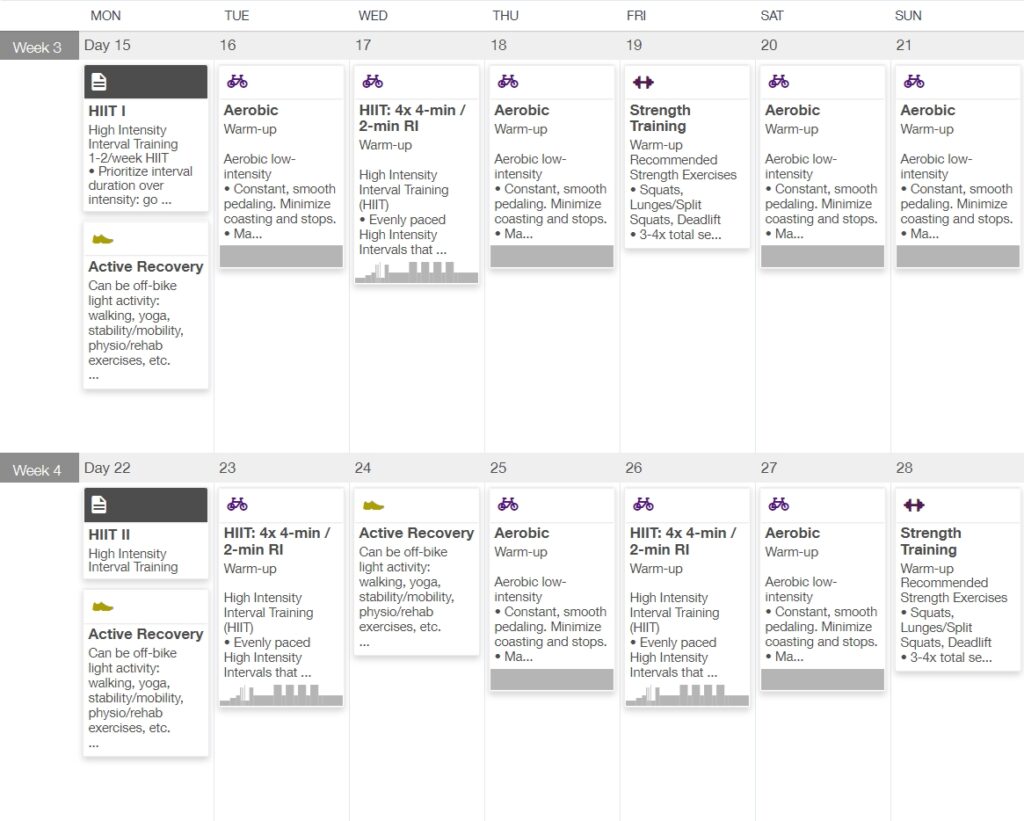

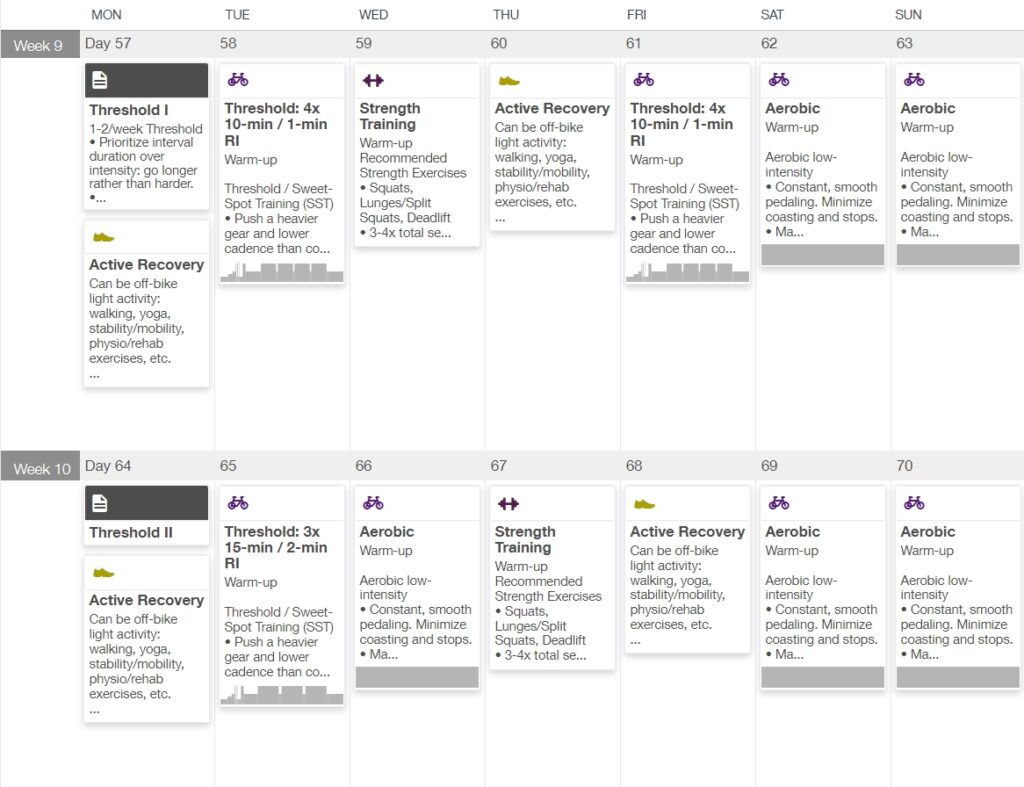

You’ll find the general structure and advice below in a janky spreadsheet. I have included a Training Peaks training plan which can act as a template with some example training weeks. This is not an out-of-the-box training plan. This is simply a template which needs to be filled in and individualized to suit our needs. The Training Peaks plan can be exported to Zwift and other virtual training platforms.

Training Plan General Information

Low-intensity Aerobic Training

Let’s talk about low-intensity aerobic training first before getting into the key high-intensity workouts, below. You may notice I haven’t included a strict low-intensity ‘base’ phase. Maybe I should (maybe I’ll update this and I will!). One reason for that is the time many people start a training plan is mid-winter when daylight hours are limited, and long low-intensity riding either outside in the cold, or indoors on a trainer is not the most pleasant or motivating activity. I usually perform my ‘base’ training phase at the end of the summer as low-structure, high-volume riding with my Garmin/Wahoo in my back pocket, just enjoying the ride and keeping the sensations feeling easy/10. Before transitioning with some well-earned recovery, then settling into a more structured winter training plan.

See my comment below to this great question about overall periodization structure for a bit more rationale for how it’s presented here. And please understand, these training blocks can be considered modular, to be done in whatever order is most appropriate to your situation.

Although aerobic/low-intensity training could be brushed off as filler between the key harder workouts, I would suggest our low-intensity training sessions are the foundation upon which an endurance training plan must be based. The simple advice for a sustainable training plan is perform one or two structured high-intensity sessions each week at most, and fill the rest of our available time with low-intensity continuous activity according to (1) how much time we have prioritized for training, and (2) – this is important – our capacity to absorb and adapt to a given training volume.

Some of us will be limited by how much time we can train. The reality is that if we only have 6-hrs each week to train, our endurance performance will probably plateau before we get to a world-class level of competition. But we can certainly maintain a relatively high performance level, as well as progressively enhance our metabolic fitness over the long-term with that amount of structured training.

Others of us will be limited more by how much training stress we can absorb and adapt to, without accumulating/compounding fatigue over the med/long-term. This might be true whether we have 6-hrs or 26-hrs each week to train. A novice to structured training probably won’t be able to tolerate too many back-to-back 26-hr training weeks right away, regardless of time availability for training and recovery. Just like anything else, we should expect to gradually progress how much training volume, stress, or load we dose ourselves with in order to progressively adapt.

The biggest question by far is ‘what is the minimum effective dose’ of low-intensity training duration? Is a 30-minute aerobic session worth it? Or should we increase the intensity? The first answer is that it depends on what our bodies are accustomed to: if we are adapted to tolerate and absorb regular 4-hour aerobic sessions, then a 1-hour session might not give us much adaptive stimulus. It might be a maintenance session at best. On the other hand, if we’re new to training or returning from an injury or time off, then 30-minutes might give us a nice beneficial training stimulus. Regardless, 30-minutes of activity is better than nothing. Even more importantly, more frequent and more consistent short sessions can be just as good, if not better than less frequent/consistent longer sessions.

No, unfortunately we can’t just increase the intensity to make up for less time availability to train. I mean, you can do whatever you enjoy doing and whatever keeps you active! But shorter duration at higher intensity is simply different from, and not a replacement for low-intensity exercise. In general, our bodies can optimize and adapt toward either improved capacity or improved efficiency, but not both simultaneously. If we only ever expose ourselves to intensity-dependent stimuli, we will likely be missing out on an optimal response across both ends of that spectrum. Low-intensity training gives us a dose of durational-dependent stimuli which are necessary for sustaining endurance performance and metabolic health.

As such, more low-intensity activity is generally better. I would suggest this includes lifestyle activity levels just as much as structured training. Metabolic health comes not just from the few hours each week of deliberate structured training, but from our baseline activity levels and energy flux through all our waking hours. Move more. Stand up right now if you can, flex some muscles and move!

Warm-up

The harder the workout, the longer the warm-up should be. The obvious purpose of a warm-up is to prime our physiology to improve both efficiency and capacity at a high relative intensity. Furthermore, our warm-up should be an opportunity to check-in physically and psychologically with how we’re feeling before giving our best effort toward a training session.

I suggest implementing a standardized warm-up protocol before every trainer workout, where we grow familiar with the sensations of each progressive effort. We can monitor how we feel on any given day, within a dynamic physiological range: about normal, worse than normal, better than normal? This should inform how we proceed with our planned training session: are we all signals go? Or does something not quite feel right? Will I be able to get the most out of my effort today? Or would I benefit from reducing my physiological stress today and reschedule the workout for later this week?

When we feel marginal, and we’re not sure which call to make, first just show up: meaning, start the planned session and see how things go. The answer might quickly become obvious, or we might continue to feel marginal. Remember, optimize for the longer-term, not for any one single workout.

I think the key prescriptive advice for a warm-up is start easier than you think. Even easier than that. Try to spin without feeling the pedals and gradually ramp up the cadence and power as the load naturally falls away even further, as things start to… warm up! Keep the load minimal until we feel the first drops of sweat. To me, that’s a good sign of a systemic vasodilation or warm-up hyperemia, and anecdotally this aligns with an increase in muscle oxygenation. Only then, proceed with the progressively higher cadence, higher intensity efforts. And take a nice long ‘warm-down’ period after the higher intensity efforts to shed any fatigue, to ensure we start our intervals with a full tank of energy. Don’t worry, the warm-up hyperemic effect will persist quite a long time.

The TrainingPeaks plan linked above includes my standardized ~20-minute warm-up protocol.

SIT: Sprint Interval Training

Sprint Interval Training (SIT) consists of a few ALL-OUT, very hard, very short, maximal efforts. All-out means that we aren’t pacing ourselves over a set duration: these are not 4x 30-sec sprints. These are all-out as hard as we can possibly go, pushing every pedal stroke maximally. And given we are going as hard as possible, we try to maintain that maximal effort as long as possible. They might be 10-seconds, they might be 40-seconds. We are prioritizing maximal intensity – or maximal energy (power) throughput – for as long as we can sustain that maximal intensity.

Please also consider safety: these should be as maximal as we can safely perform, whether they are out on an empty stretch of road, or on our trainer at home. Please make sure you don’t break your bike, body, or trainer. I have crashed myself trying to perform this workout. I felt very stupid, and was very glad the road was empty for the sake of both my fragile body, and my fragile ego. We’ll get more familiar with these maximal efforts as we go. Start conservative and build your comfort level.

These are really a better outdoor workout than trainer workout. We can perform sprints during a longer low-intensity ride, taking advantage of the occasional familiar, empty road to send a sprint, then spinning around for a longer recovery period. Say, throw in a sprint every 20-30 minutes during a 2-3 hour ride. On the trainer, I recommend performing seated sprints to minimize lateral forces on our equipment. Start from a high resistance and low cadence, and accelerate a big gear up to speed as fast as possible. Careful with wheel-on trainers, we might get rear wheel slip. And basic trainers (magnetic, fluid resistance) may not have enough resistance to go properly all-out for bigger powerhouses. Instead, we can work on our track sprinter technique and focus on a high and stable cadence.

SIT is by far the most time-efficient training method for improving fitness, primarily via adaptations to peripheral working muscle. ie. mitochondrial respiration and function, angiogenesis and capillarization, and neuromuscular coordination. However, it comes at a potential cost of reduced fatigue resistance and possibly metabolic efficiency (remember that capacity/efficiency trade-off?). SIT is also very fatiguing relative to it’s very small training volume, so we would not be able to just repeat this workout (nor any single workout) forever.

I find SIT is a good protocol to start for the first couple weeks of a training plan. The efforts are very hard, but very short. We don’t need to maintain focus for long. It’s also a good way to psychologically release some energy! And we will very likely see some rapid, obvious improvements to our power output after a few sessions, which is highly motivating.

What if our goals & priorities don’t include sprinting? I would suggest SIT is still important for general fitness. Maximal efforts hit larger motor units and different muscle groups that can be missed with lower intensity training. SIT gives us an incredibly valuable combination of strength, speed, metabolic stimuli, and neuromuscular coordination that are difficult to achieve any other way. These are the very aspects that we lose most rapidly as we age, so I think SIT is important for both performance and health/fitness goals.

HIIT: High Intensity Interval Training

High-intensity interval training (HIIT) is our bread and butter for performance, fitness, and metabolic health. This is our classic ‘VO2max training’. I prefer longer HIIT bouts with intervals greater than 4-minutes. These are hard, at an intensity above our maximum metabolic threshold (FTP, CP, anaerobic threshold, lactate threshold, etc.) but not maximal. As long as we are working within this severe intensity domain, we don’t need to maximize intensity. Instead we should be aiming to extend the duration of each interval/bout. The duration we spend within this intensity domain appears to be most effective to improve both performance and general fitness outcomes. HIIT is the most effective protocol for improving VO2max, which is just one (arguably overrated) physiological parameter.

Furthermore, the rest intervals are brief, at 2:1 work/rest ratio. This means we very likely cannot complete a full workout of (eg.) 4x 5-minutes if our first 5-minute repetition is maximal. We should be aiming to find the highest workload that we can sustain for the full workout duration, without needing to reduce power output, and which doesn’t end up as a maximal effort by the end. Something that leaves us with half a rep left in the tank, so to speak. That we could have gone harder or longer if we absolutely needed to.. but we don’t need to, so save that energy for the next workout!

Remember, we are optimizing for consistency across all workouts, not trying to maximize any single workout.

I have programmed a 6-week HIIT block with taper/recovery in weeks 3 and 6, as I feel this is the heart of the training program. But of course, like everything else in this outline, the expectation is that we should change and adapt the specifics to suit our own requirements. Some athletes will reach a plateau in adaptive benefit earlier, some later. Some will need recovery, or de-load, or taper weeks more often, and some less often. Some will progress the workout prescription faster (eg. add 1-min to every work bout each week), and some slower (eg. a full 3-4 week training block performing the same workout protocol).

Threshold Training

Riding below and close to our maximum metabolic steady-state threshold (FTP, CP, anaerobic, lactate, ventilatory, deoxygenation, or however else we want to approximate it) is, I think, the most appropriate protocol for building fatigue resistance. However, this comes with a strong caveat that the intensity must actually be below our metabolic threshold, which is not itself a single line or power value, but is a constantly moving, blurry, transitional ‘grey zone’ where the metabolic sustainability of the external workload changes from sustainable steady-state to non-sustainable gradual drift toward task intolerance.

That is to say, it’s better to hedge low, say by 10%, than to overshoot the target by even 2%. This is because above and below this transition, a completely different metabolic milieu, different adaptive stimuli, and different fatigue profile develops.

Threshold training can be performed continuously for long durations (10+ minutes). I recommend a ~10:1 work/rest ratio, more as a brief release of intramuscular tension and a chance to mentally refocus. If we feel like we need longer rests or more often, we are probably working at too high an intensity. We should be aiming to accumulate 40+ minutes of work at a sustainable power output that feels like we could complete the entire workout duration without rest if we had to (but we don’t have to!)

Strength Training

My basic advice is: do strength training of some kind, do it regularly (1+/week), and do it consistently year round. Use whatever tools you have access to and are comfortable with: bodyweight, terrain (eg. box jumps outside), heavy bands, heavy inanimate (or animate!) objects around the house, dumbbells, kettlebells, barbells, strength machines.. whatever. (Links above to some of my super secret curated playlist of home workout options, including some janky videos of my own that were never meant for wider distribution)

Resistance training will make us more durable and resilient to injury. Improved resiliency means greater capacity to absorb training load and more consistent training. More consistent training makes us faster. Therefore resistance/strength training will make us faster. Strength training won’t increase our VO2max. That’s simply the wrong outcome measure to focus on to identify the benefits.