Image Credit: Sporttechie

Major sports leagues have been using data to improve athletic performance, training methods, recovery, and fan engagement for years. But as technologies to track these athletes become more advanced and ubiquitous, they’re creating opportunities to engage with biological data in new ways.

At yesterday’s SportTechie PRO DAY focused on athlete tracking, experts weighed in on the state of biometrics and gave their best predictions on where the industry is headed, including the potential to monetize this data in the near future for sports betting.

“I feel like I was a pioneer who got shot by many arrows and had a few failed companies,” says Dr. Phil Cheetham, director of sports tech and innovation at the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee (USOPC). “But I think the future looks bright now for biomechanics.”

Defining Biometrics in Sports

Biometrics are used in sports to identify talent, injury risk, and estimate readiness, according to Sparta Science founder Dr. Phil Wagner.

“The best way to think about it is as a Where’s Waldo-type scenario. It’s trying to find something in a very noisy environment,” he says. “And that Waldo can be anything from the best athlete to an injury risk or the optimal performance characteristic for that individual.”

Wagner says “there’s a need for better biometrics and talent identification.” Using the NFL as an example, he says that over the past seven years of the league’s first-round draft picks, just 53% “have panned out and been successful.”

JOIN THE CLUB: SportTechie PRO Members Get Free Access to Our PRO DAYS

Biometrics can help to identify who’s at risk for injuries and when they’re able to safely return, and they can gauge athlete readiness to determine when they’ll be performing at an optimal level. Wearables have been especially helpful for the latter during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“A lot of times what we see particularly more recently with COVID are wearables and monitoring systems to know what’s the optimal stimulus or optimal load for this individual,” Wagner says.

As precise, granular data about injuries continues to build, biometrics are providing clarity around injuries and recovery time.

“The recovery from concussion is far longer than we thought,” Wagner says. “And the way we’re able to identify that metrics are just better, more objective, granular technology. The challenge with injuries, whether it’s concussion or others, is they don’t happen very often. So we’ve got to aggregate that data in order to be predicted.”

Movement Matters

As co-founder of The Titleist Performance Institute, a 30-acre performance, and development facility in Oceanside, Calif., Dr. Greg Rose says he’s “always trying to make players and coaches understand the link between their body and their sport.”

While the TPI primarily serves the world’s best golfers, it also trains football, tennis, lacrosse, and baseball players in its state-of-the-art facility that includes a 20-camera Raptor system for motion analysis and a 12-sensor Polhemus Electromagnetic System that tracks athletes through space.

Rose says he believes movement is a “vital sign” in athletics. To measure this, his team uses functional movement screens, which helps to evaluate an athlete’s movement patterns.

Using motion capture, TPI looks at the way an athlete squats, flexes, or balances. It can also dive into sports-specific questions, such as whether an athlete can disassociate their upper body from their lower body, or the range of motion in their wrists. After that, Rose and his team watch the player perform their sport or skill, then basically “match them together” to understand their full range of movement.

“Movement screening doesn’t tell me what you can or can’t do. It just helps me explain why you do it that way,” he says. “In other words, the reason we do movement screening is not to say, ‘Oh, if you can’t do this, you can’t be a Major League Baseball pitcher,’ because I believe you can always figure out how to pitch. But this helps me understand why you do it that way. And maybe I should encourage that as a coach and not try and stop you because maybe that’s the most efficient for your body.”

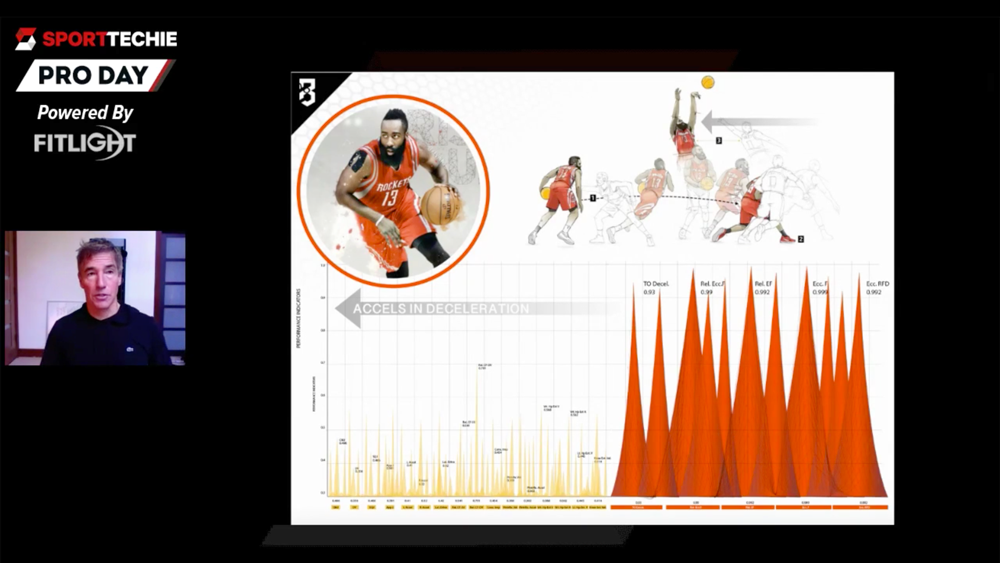

Marcus Elliot, the founder of P3 Applied Sports Science, says the way we move, jump, land, and cut have “huge implications in what happens to our body.”

At P3’s performance lab, athlete movement is calculated using motion capture alongside measurements of vertical and lateral force.

“If an athlete jumps 38 inches, where’s that force coming from? Is that a system that can survive long term? Is there too much force going through one leg or one joint?” says Elliot. “When there is, we can predictably estimate injury risk to these joints.”

Elliot says that nearly 60% of active players in the NBA have been through one of P3’s facilities. That includes Zion Williamson, power forward for the New Orleans Pelicans, whom Elliot calls a “force beast.”

“Zion actually creates more raw force when he jumps than any other athlete I’ve ever assessed,” he says. “He literally pushes harder against the Earth when he jumps. He’s a really, really rare athlete.”

While Williamson missed the beginning of the 2019-20 NBA season because of a knee injury, Elliot says biomechanical movement data can help keep him healthy in the future, or put him back together more efficiently should he become injured again.

Hydration Impacts Performance in Key Ways

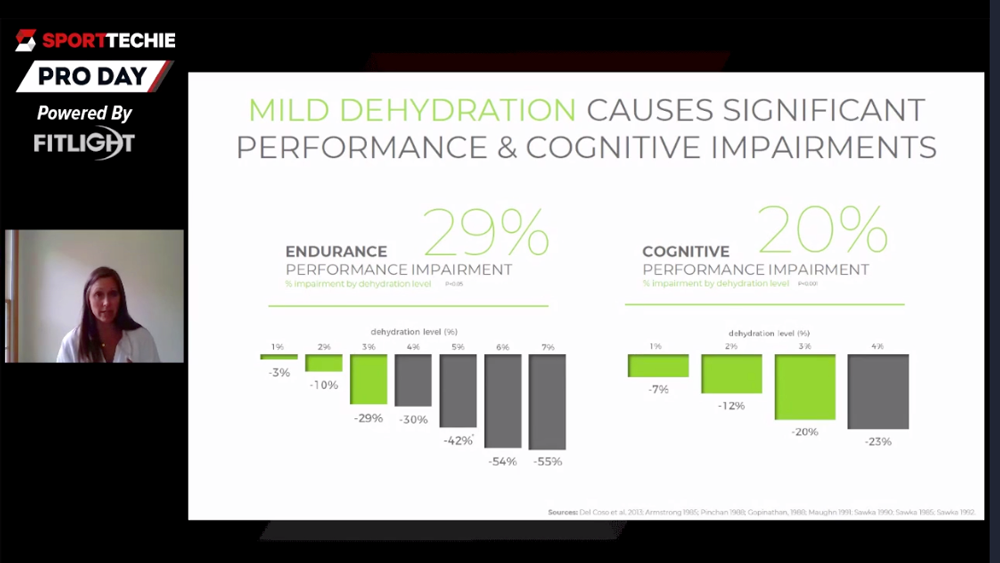

People can become dangerously dehydrated in fewer than 15 minutes, according to Meredith Cass, the founder, and CEO of NIX Biosensors, which makes performance hydration devices.

Athletes who are running, even if it’s just soccer or football players going up and down the field, will be 29% slower when they’re in a mild dehydration range, she says.

Hydration is often measured by using someone’s first or perceived sweat rate as an indicator of how much fluid they should be drinking. However, Cass says it’s only accurate to about 50%.

“It basically amounts to guessing and we see huge issues especially at the severe end of the dehydration spectrum, which can often lead to heat illness or heat injury, and very severe cases can lead to death,” she says.

Nix’s sweat-based sensor measures subtle changes in biomarkers present in sweat to provide real-time measurements of an athlete’s level of hydration. By measuring things such as fluid losses, electrolyte losses, current hydration status, and core body temperature, Nix’s algorithms can provide athletes information on exactly how much fluid they should be consuming to avoid cognitive impairment or physical injury.

“Whether it’s a marathoner or a football player, a soldier or a firefighter, we can tell that individual what their needs are in real-time, so that they can start to understand if they’re getting into a danger zone,” she says.

Lighting the Way

While many of the biomechanical training tools mentioned so far have been designed around the individual experience, other technologies are aiming to do this at scale for entire teams at once.

The FITLIGHT system is a wireless training tool that uses LED lights and targets that a user needs to deactivate during their session to determine reaction times and accuracy. Data collected during the session is automatically sent to a tablet for analysis.

“I can not only train individuals but also have training protocol for an entire team,” says Matteo Masucci, director of FITLIGHT Lab.

The system trains athletes to use an external focus of attention rather than internal, where they might be distracted with how and why they’re doing something, which can impair performance.

“When you focus internally, you focus on your feet, you focus on your arms, you focus on the mechanics,” says Masucci. “When you do so you’re actually disrupting the motion because you’re overthinking what you have to do. There is more fluidity in the execution when a player is on an external focus of attention.”

Meanwhile, Beyond Sports is building 3D simulations of actual games using positional tracking data that many teams are using for immersive film review. It collects coordinates off objects on the field at a rate of roughly 25 frames per second. Afterward, pro teams like Dutch team AZ Alkmaar use Beyond Sports’ match analysis training suite to learn from their mistakes and understand their decisions on the pitch.

Soccer academies feeding into some of the Netherlands’ elite clubs have benefited from reviewing AZ Alkmaar game film in a virtual reality environment.

“That has allowed them to understand how fast the professional game is and how fast the elite players are playing, and it gave them the possibility to make decisions faster after this training,” says Konstantin Dieterle, head of business development at Beyond Sports.

The Power of Data

With more sensors attached to more athletes in the name of athletic performance, athletes should educate themselves on what is being collected and how it’s being used, according to David Foster, deputy general counsel at the NBA Players Association who sits on the NBA-NBPA Wearables Committee.

“One of the main things that we try to tell all the athletes is that if you’re going to use a device or if your team is going to use a device and capture your data, make sure you get a copy of the data,” says Foster.

“As much as you want to rely on the team, you should educate yourself on what’s being collected and how we want to be used,” he says. “I always tell them that this is like any other part of your profession, you should pay attention and you should be involved.”

With fractions of a second in the 40-yard dash potentially determining a pro football player’s starting salary or whether a kid gets into a college program, biometric data is becoming essential.

“For every athlete, data is a marketing tool as much as it is a self-development tool,” says Mike Weinstein founder and CEO of Zybek Sports, a laser timing system used by the NFL combine. “Athletes, whether they’re at the high school level or all the way up to the pros, can use this data to help better market themselves. You look at anybody at the NFL combine. If they get really good 40-yard dash numbers, that’s what they’re bragging about.”

There’s also the potential for athletes to monetize their own data down the road, possibly by allowing their data to be used in sports betting or fantasy games.

“There is definitely the potential there, but we just haven’t figured out actually how to commercialize it,” says Kristen Holmes, VP of performance at wearable company Whoop and a former Team USA field hockey player and NCAA champion coach.

“But I think there is a world there, where you have an individual athlete who decides that they want to put their data out there to be bet on and they get a cut of it,” she says. “I think there is a world where you’re seeing heart rate data or recovery data leading into a game. You can see heart rate data as a pro golfer approaches a putt, and fans betting on it in real-time based on some of that biometric feedback.”

The Future of Biometrics

Sensors, wearables, cameras and GPS are all being used in varying capacities to track biometrics. But Dr. Phil Cheetham, director of sports tech and innovation at the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee, says the future of this technology lies within smart cameras that can track and analyze all at once.

Biometric technology must be “non-intrusive and invisible” to the athlete, easy to use and simple to understand, says Cheetham, who gave the closing keynote at the SportTechie PRO DAY and also participated in an exclusive fireside chat with SportTechie PRO members.

“The magic camera that automatically tracks motion is the holy grail; it’s going to advance biomechanics,” he says. “I think biomechanics has been stuck in the weeds because of the expense and the complexity of the technology in the past.”

Once the system is powerful enough to do this, the next goal will be to synchronize and overlay data with video.

“That’s the way we have to sugarcoat it for the athletes, we have to spoon-feed it by having the video of their performance and overlaying key points and key pieces of data that don’t confound them so that they are impactful and very clear,” he says.

Authored By:

Jen Booton, and published on the Sporttechie site. View Here.